ONE SITE—TWO VISIONS | Finessing Form-Based Code

The Columbia Pike Form-Based Code (FBC) provides a pathway for streamlining the development entitlements process via prescriptive design requirements intended to transform auto-oriented corridors into walkable, mixed-use main streets.

The 2600 block of Columbia Pike—where MV+A has designed two distinct projects for two different clients—offers a revealing case study in how the same code can accommodate projects of divergent retail programs and ancillary service and access requirements.

Both schemes embrace the FBC’s intent for a pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use environment, yet each illustrates how the same regulatory framework can utilized to achieve innovative outcomes. The contrast lies not expressly in compliance, but also with application—how each design mediates the code’s urban design goals with site conditions, tenant requirements, and the evolving character of Columbia Pike itself.

NOTE: Both projects were developed for the same mid-block parcel along Columbia Pike at different points in time. Neither project has been constructed. The Elliott (2022) has since been discontinued, while 2600 Columbia Pike (2025) represents the current design advancing through the FBC approval process.

Project Status Overview

Project Year Status Client

The Elliott 2022 Unbuilt | Not Moving Forward Insight Property Group

Columbia Pike 2025 Active Project Kennedy Wilson

A TALE of TWO RETAIL STRATEGIES and a STEEPLY SLOPING SITE

Located on the same mid-block parcel along Columbia Pike, The Elliott and 2600 Columbia Pike represent two distinct responses to the same form-based code framework. Both proposals deliver a similar residential program, but diverge significantly in their ground-floor strategies—differences shaped as much by market realities as by code.

The Elliott, developed by Insight Property Group, was anchored by a pre-existing pharmacy lease and an early-committed full-service grocer. These in-place tenant agreements effectively set the retail program from the outset, requiring independent loading, service, and parking solutions that produced a complex, multi-bay podium.

By contrast, 2600 Columbia Pike—developed by Toll Brothers Apartment Living—replaces the large-format anchors with a more flexible lineup of smaller, inline storefronts. This shift simplifies the structure and logistics while strengthening the project’s relationship to the street, the surrounding block, and the placemaking goals of the Columbia Pike Form-Based Code.

Across both efforts, the steeply sloping site demanded inventive solutions for program distribution, circulation, and engagement with the public realm—each revealing different lessons about designing under the same code on the same piece of ground.

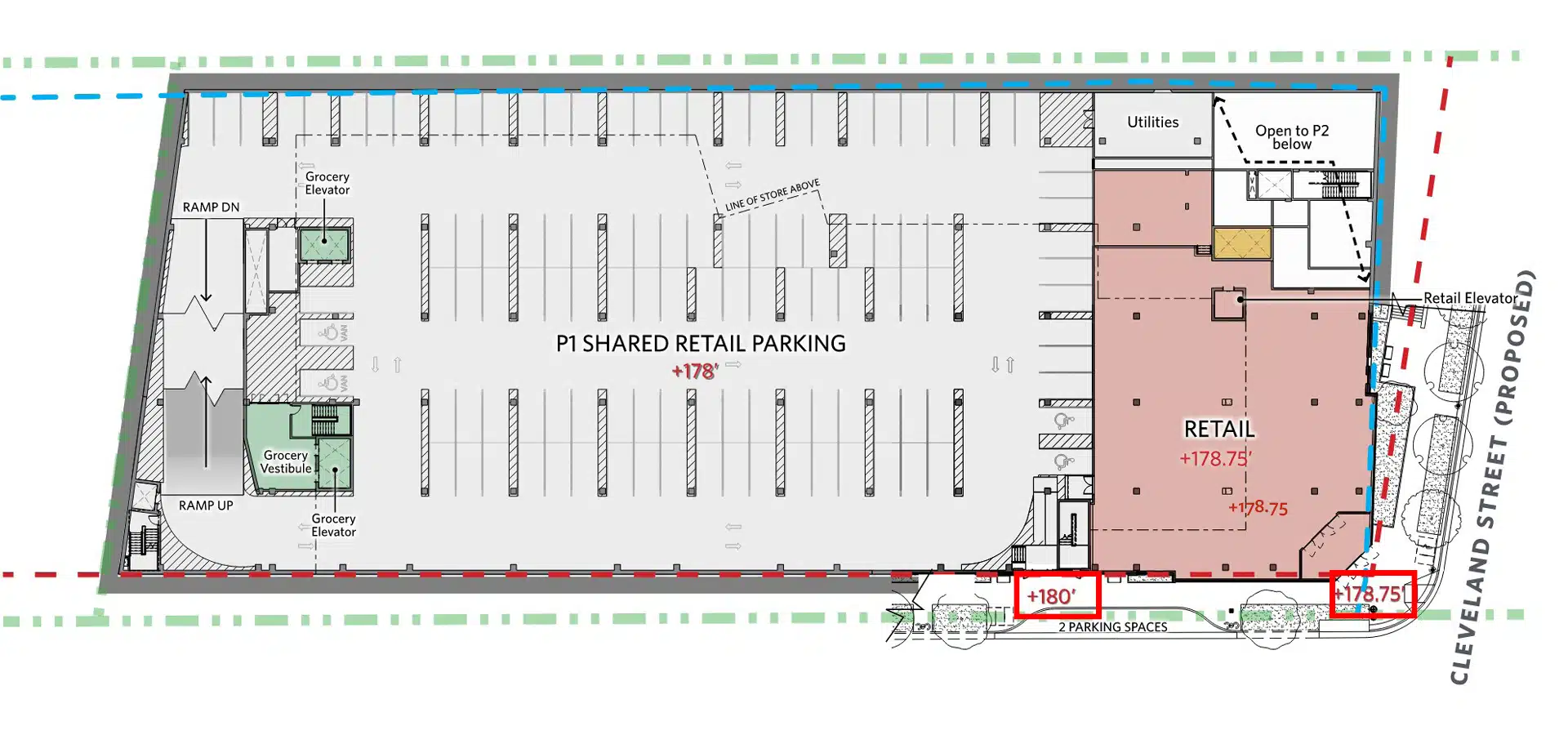

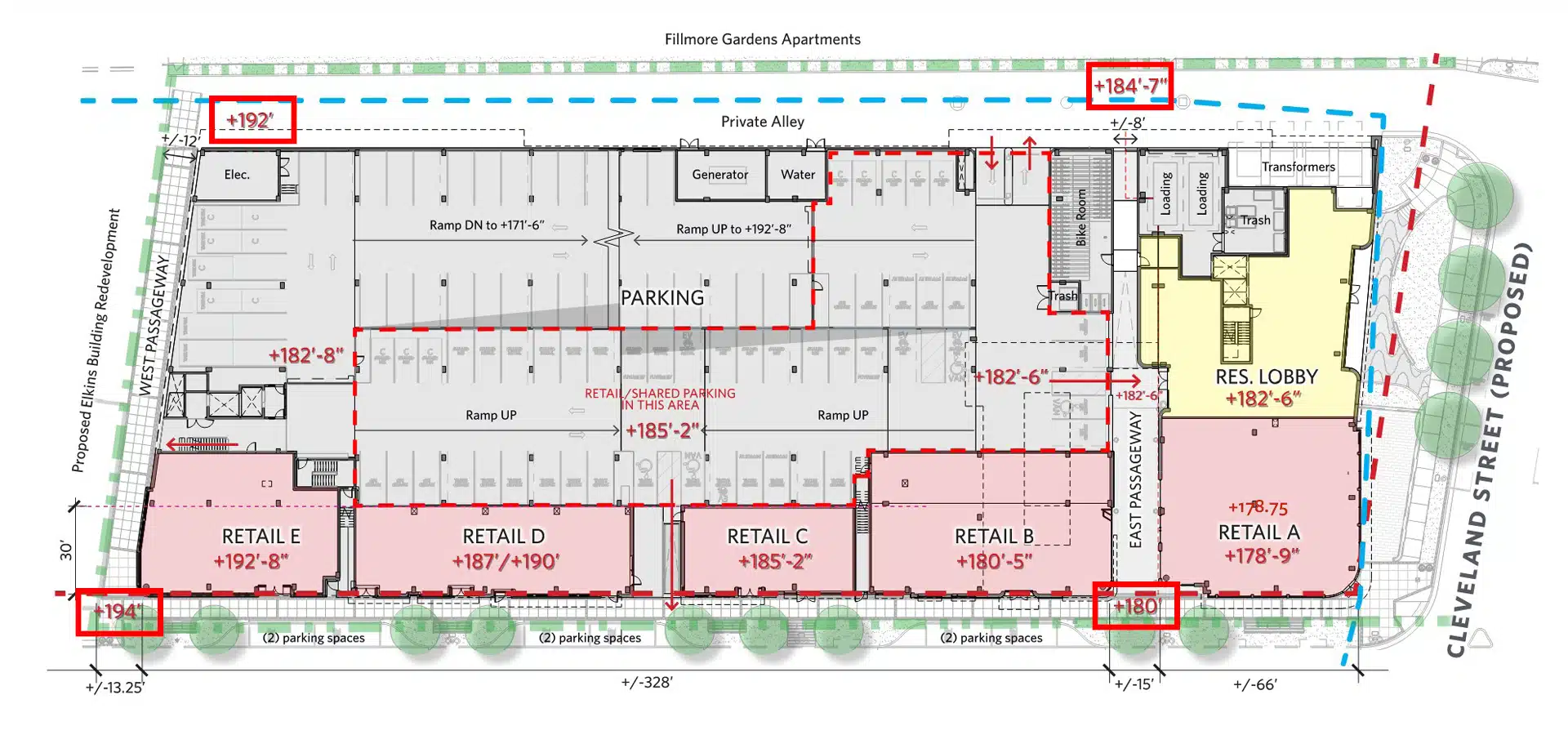

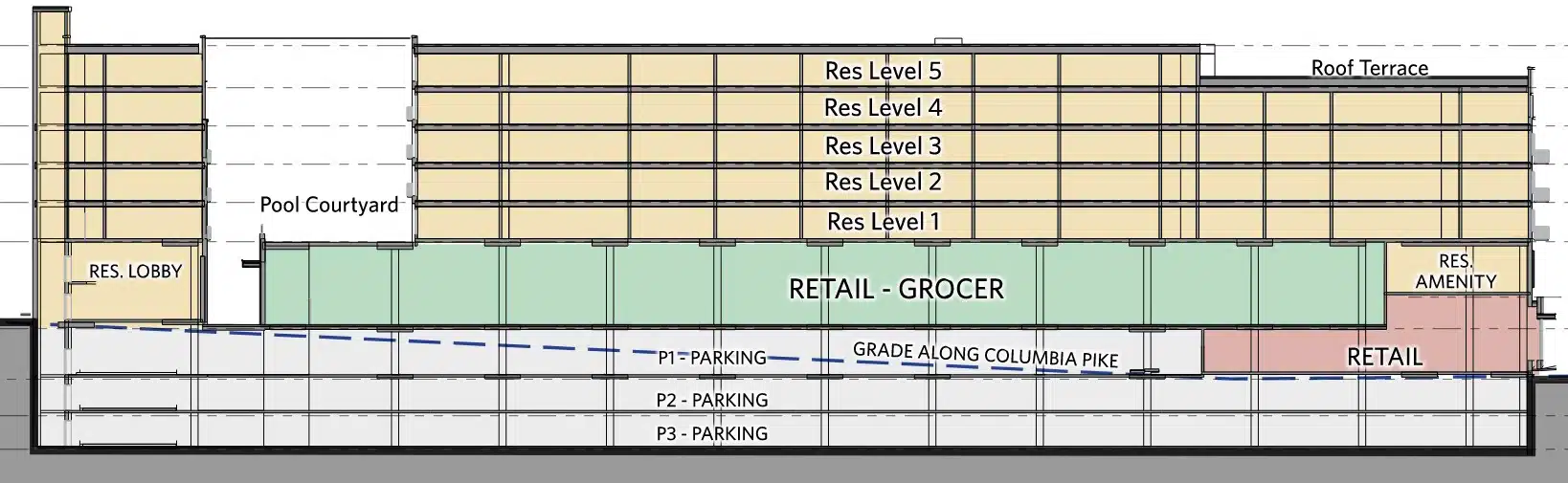

The Elliott | Unbuilt Concept [2022] The ground floor retail was established by the grade at the southwest corner of the site [+194’ / see lower left ]. Setting the grocery retail at this level afforded the opportunity to locate retail parking on the level below while providing parking and service access in such a way that capitalized upon the grading along the rear drive. These measures afforded a continuous pedestrian experience the full length of Columbia Pike—free of curb cuts and enhanced by a rich building material palette.

Ground-Floor Activation and Pedestrian Experience

FBC Intent: The Commercial Centers FBC emphasizes pedestrian permeability and human-scale block patterns, limiting block lengths and requiring mid-block connections or alleys to break down large parcels. Active, transparent ground floors are essential to Columbia Pike’s identity as a revitalized “main street.” The code assumes continuous retail edges with generous storefront transparency and limited curb cuts.

The Elliott: The large floorplate requirements of the major and junior retail anchor tenants, along with their staggered levels, afforded limited opportunities to provide truly activated store frontage along the length of Columbia Pike. To compensate, painstaking attention was paid to the facade design and materiality—taking every opportunity to highlight non-retail building thresholds, from the residential lobby to the public parking entrance.

2600 Columbia Pike: The shift to smaller, inline retail allowed more frequent entries, glazing breaks, and visual continuity with the streetscape. The design optimizes the FBC’s allowance for varied frontage types and smaller retail modules.

Take-Away: While the FBC’s emphasis on active frontage and pedestrian continuity remains sound, its framework also allows flexibility for larger-format retailers—so long as they contribute to the street’s visual and experiential rhythm. The challenge lies not in the code itself, but in how projects interpret its intent. Economic and leasing realities often privilege larger anchors that can disrupt fine-grain transparency, yet thoughtful design can reconcile scale and activation. The lesson is that “activation” cannot be measured by frontage length alone—it depends on scale, permeability, and design nuance. Smaller, secondary entries, layered façades, and ancillary access points enable even large tenants to uphold the FBC’s main street vision.

Massing, Materiality + Courtyard Configuration Along CP

FBC Context: While the Columbia Pike Form-Based Code reinforces a continuous street wall through required building lines (RBLs) and build-to standards, it also incorporates several provisions that encourage façade articulation and open-space relief. Building envelope standards call for periodic façade interruptions, a minimum 15% open contiguous lot area, and through-block pedestrian passages for any block face exceeding 400 feet in length. Together, these measures aim to prevent overly long or monolithic frontages and to maintain pedestrian permeability throughout each block. Yet despite these allowances, most mixed-use residential projects along the Pike have defaulted to fully internalized courtyards—producing continuous, opaque street walls and minimizing outward engagement with the public realm.

The Elliott: In response to these requirements The Elliott deployed an outward facing pool terrace to afford open-air solar exposure for both the pool terrace and the ground level pedestrian passage while modulating the perceived scale of the building. A similar strategy was applied to an upper level amenity courtyard on the north side of the building adding additional refinement to the building massing.

2600 Columbia Pike: While the central amenity courtyard is fully internalized, the pool terrace redeploys the Elliott’s strategy to the eastern end of Columbia Pike achieving the same end goals of building massing and scale modulation.

Take-Away: The Columbia Pike FBC permits—and arguably encourages—relief within the street wall through its massing, open-space, and block-length provisions. However, a preference for expedient and easily replicable building types has led to a proliferation of inward-facing courtyard building types whose scale and opacity undermine the code’s goals for fine-grain urbanism. Outward-facing courtyards like those designed by MV+A demonstrate how compliance and creativity can coexist, transforming code flexibility into active, light-filled, and contextually responsive architecture.

CONCLUSION

The Columbia Pike Form-Based Code continues to stand as a thoughtful model for corridor revitalization, but this case study makes clear that regulation alone cannot script great streets. True urban quality emerges from the interplay of code, context, and creativity. Each project must process intent through the lens of real economics, evolving retail patterns, and human experience.

Both The Elliott and 2600 Columbia Pike reveal that form-based codes, no matter how prescriptive, work best not as templates but as frameworks for adaptation—between policy and practice, design aspiration and financial feasibility. When applied with sensitivity, they can transform constraint into opportunity, balancing predictability with invention. In the case of both projects, the process and pathway offered via the Columbia Pike FBC have proven reliably consistent.

As communities across the region continue to recalibrate zoning and design standards to address affordability, walkability, and resilience, Columbia Pike reminds us that codes do not build cities—people do. The enduring challenge is to ensure that our regulatory tools remain flexible enough to accommodate innovation while steadfast enough to preserve the civic and human qualities that make places worth inhabiting.