HOUSING FUTURES | Part I

There is little debate that the US is experiencing a serious housing crisis. However, there is considerable discussion about defining and responding to this ‘housing crisis’.

In this first installation of ‘Housing Futures’, we will attempt to present a concise overview of the issues at play along with some of the varying perspectives that make this such a difficult problem to tackle. In terms of potential responses, this first issue will focus on ‘Missing Middle Housing’ and its potential to respond to a wide range of housing concerns.

In future issues of this series, we will be discussing other promising options such as Point-Access-Block Housing, Mass Timber, Office to Residential Conversion, and more—so please stay tuned!

Supply, Demand, and Data

The disparity between housing supply and demand is probably the single most difficult part of the equation to define, largely because we have done such a poor job establishing adequate tracking metrics. Conservative estimates suggest a shortfall of 1.9 million homes [Moody’s Analytics] while more assertive estimates place the number closer to 6.5 million [Market Watch].

One can see how confusing such data becomes when a city like Los Angeles announces that it is at a deficit of 400,000 housing units [NY Times]—that’s 6% of the estimated worst-case national scenario. To complicate things further, there is little meaningful data quantifying the impact of natural disasters on the national housing supply. In the US over 3 million people were displaced in 2022—temporarily, at least—and in California, the damage to residential properties topped $1billion. Evictions and foreclosures, building health and safety violations, legal disputes, and many other minutiae can also impact the housing supply.

It is said that if you can’t measure something, you can’t fix it. Clearly, we need to do better in this arena if we ever hope to effectively shine a light on the urgency of this issue.

Surmising the Shortage

Between 1940, when the very first US Housing Census was conducted, and 1990, there was an increase in the national housing stock from 37 to 102 million housing units, a gain of 173 percent—outpacing the 88% increase in population during the same period [US Census Bureau]. On average, the housing supply increased by 20% every decade over a fifty-year period. After 1990, the ten-year average increase fell to around 10% until 2010 when it reached +/-130 million units. Between 2010 and 2020 this number only increased by 10 million units—a ten-year average of just under 1% [American Housing Survey].

Suffice it to say, the sub-prime mortgage crisis and subsequent Great Recession played considerable roles in this stagnation of housing supply growth. But the real shortage, hidden within the statistics above, relates to housing options. Since 1940, the vast majority of housing supply has come in the form of single-family homes—by design. Prior to 1940, a majority of housing units were located within the boundaries of central cities; by 1970, there were more people living in suburbs than in cities. While the socio-economic implications of America’s suburbanization are complex and way beyond the confines of this brief, it is estimated that as of today, 75% of all residentially zoned neighborhoods in the US are designated strictly for single-family housing.

Within this context, alternative types of housing units are typically relegated to mid- and high-rise buildings, often located along primary transit corridors—away from single-family neighborhoods. This affects a large number of moderate income households, ranging from young professionals and growing families, to older adults with changing lifestyles—not to mention the vast majority of those in lower income brackets. The bottom line is that the notion of shortage relates equally to that of options.

Missing Middle Housing is not new. If you walk around long-established and long cherished residential neighborhoods like Park Slope in Brooklyn, Lincoln Park in Chicago, or Elmwood in Berkley, you will find the tried-and-true originals: buildings that at first glance appear like their single-family neighbors but, upon closer inspection, may have two front doors, or an entrance lobby, a basement entry, or multiple utility meters. In short, multifamily housing designed to integrate well with single-family and other mixes of housing types. Examples include duplexes [side-by-side and stacked], triplexes, courtyard apartments, townhouses, and more.

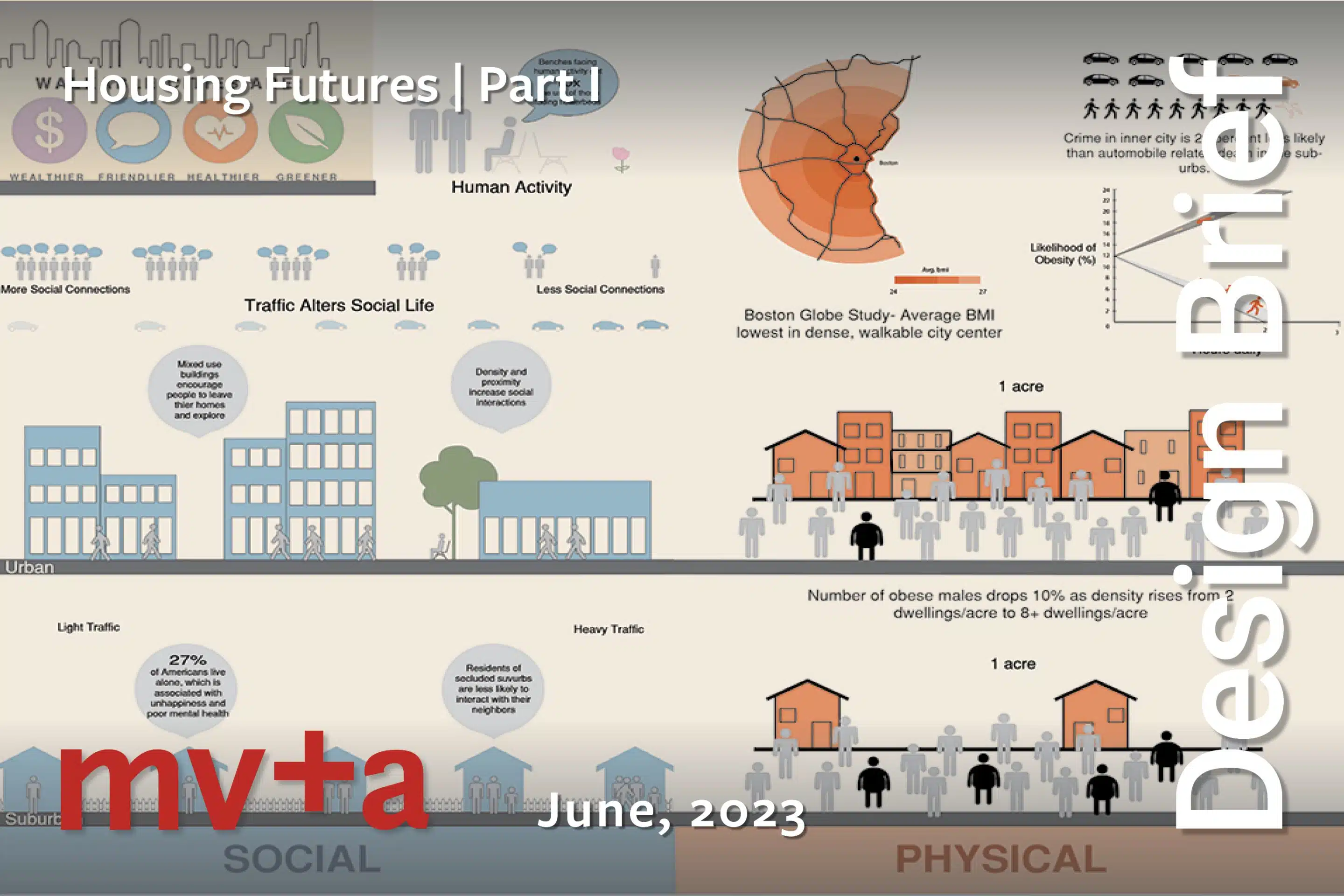

With a thoughtfully programed mix of unit types and a graduated approach to neighborhood density, Missing Middle provides choices for ranging household types as well as ranging income levels. It affords opportunities to stay in a preferred neighborhood as one’s lifestyle needs change. Missing Middle also contributes to the densities required to support public transit and the amenities and services that keep community main streets vibrant and economically feasible.

“Missing” relates to the fact that while this approach to housing was once the norm, and central to city planning prior to the automobile. We have built very little of it since, and it represents a very small percentage of the national housing supply. “Middle’ has two particular implications. First and foremost, it relates to scale—the middle scale of residential buildings, between single-family homes and mid-to high-rise apartment or condo buildings. Second, it is related to attainability—middle income households [defined as 60 to 110% of average median household income] that do not rely on subsidies make up a significant number of those most affected by the shortage and those most likely to benefit from expanded housing options. This not to say that Missing Middle cannot be successfully adapted to both higher-end and subsidized market sectors, because it is a highly adaptable approach.

Central to Missing Middle is the concept of ‘walkability’. In contrast to the auto-centric disposition of suburban living, communities that successfully include Missing Middle support urban, main street experiences at a neighborhood scale, as opposed to a big-city scale. They provides the density required to support transit alternatives [average: 16 dwelling units / acre] and promote communal public experiences—from farmers markets to community events. In short, they contribute to building strong, resilient communities. There is considerable pent-up demand for this type of residential development. According to the National Association of Realtors, 63% of households surveyed preferred to live within a walkable community.

Navigating Change

Given the tremendous success that these historic housing types have enjoyed across the country, lending considerable appeal to neighborhoods now considered highly desirable, one might assume that their reintroduction into the planning process would be a no-brainer. Unfortunately, nothing could be further from the truth.

A notable majority of single-family homeowners perceive Missing Middle and, more importantly, increased density in the form of multifamily housing, as a threat to property values, security, and quality of life—just to mention a few of the most common objections. The fact of the matter is that Missing Middle has the potential to greatly improve all of the above and more. What is key in this discussion is clearly articulating and demonstrating the parameters and variables that constitute ‘best practices’, emphasizing the benefits, and avoiding hot-button terms like density, multifamily, affordable housing, and rezoning. Parking requirements is another hot-button issue that needs to be tactfully addressed.

The ranging scale of what constitutes single-family housing is important to demonstrate, in that there is not one-size that fits all and that different household have different needs—from one bedroom to three or more. Within this context it is possible to demonstrate that a 2-1/2 story home within a very specific building footprint range, could easily accommodate a variety of dwelling units within the same building comparatively configured as a single-family home. Focusing on attainability [over affordability] and the fact that many households neither need nor may be able to afford single-family housing options is critical. Once community stakeholders understand that Missing Middle is not the same as mid-rise multifamily and that it is not specifically tied to affordability but rather attainability, the potential for proactive and productive dialog greatly increases.

While the ‘Missing Middle’ conversation has been going on for some time now, it has only recently gathered momentum and captured the imagination of a broader public. Major rezoning efforts in Minneapolis, Seattle, and Portland have inspired similar efforts to expand housing options in Montgomery and Arlington Counties here in the Washington, DC Region. While the public response has been varied, it has been vigorous and heavily attended; surely a good sign that people are starting to pay attention.