CODES, COSTS + CRAFT: Sticking up for Stick-Built, Pt. 1

‘Stick-built’ means different things to different people. In the present context, we will use the term to refer to multifamily housing built under the Type III + Type V construction classifications—aka: wood platform framing [‘stick’] over a concrete podium structure.

For those in-the-know, ‘stick built’ has something of a mixed reputation. Within the current multifamily home building market, it is the most widely utilized construction type and given the current housing boom, has come under considerable scrutiny. Most of this scrutiny falls within the realm of aesthetics, but other areas of inquiry include life-safety as well as environmental sustainability and resilience. Independent of the point of view, most publicly aired discussions surrounding stick-built projects fail to present a fully vetted review of the various socio-economic circumstances that have led to its wide-spread adoption as a preferred method of construction. As the story goes, there is a tendency to look for simple answers to complex questions.

To better understand the pros + cons of stick-built, one might parse the circumstances into three categories: a) housing supply + demand and trends, b) an abbreviated history of building codes, and c) construction materials + methods and environmental impact.

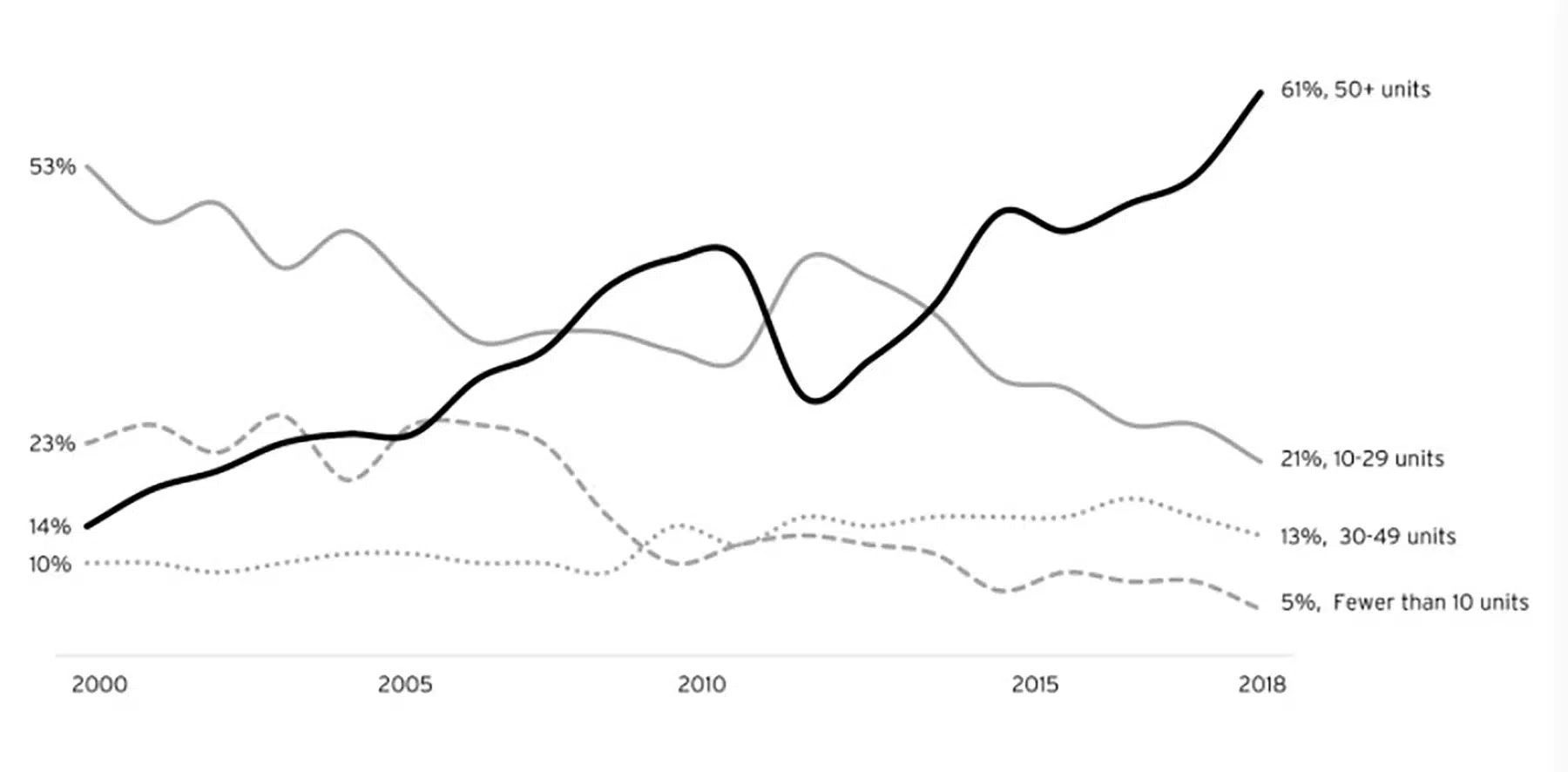

Housing Supply + Demand and Trends: the historic economic recovery and expansion of the past decade-plus have resulted in an increased demand in rental housing that has considerably surpassed the available supply. This has led to increases in rent that have surpassed requisite gains in household income. Coincidently, there has been an unprecedented increase in high-income renters during this period, subsequently affecting pressures on middle and low-income renters. This situation is further complicated by the economic impacts of the pandemic that have exposed ‘housing insecurity’ for the public health crisis that it is. On a side note, while many industries have achieved record levels of increased productivity during this period, residential construction has not been one of them [RSMeans | 2021].

Countless white-papers have been presented in the service of analyzing the component costs of multi-family housing; namely: land [10-20%], hard [50-70%] and soft [20-30%] costs—often while contrasting the differences in cost between low-rise [$150 – 225 SF], mid-rise [$175 – 250 SF], and high-rise [$225 – 400+ SF] construction types [Brookings | 2020]. Within this context, stick-built construction has been identified as the most efficient and cost-effective approach to creating more—and more affordable—multifamily housing that will affectively respond to the broadest set of burgeoning market conditions.

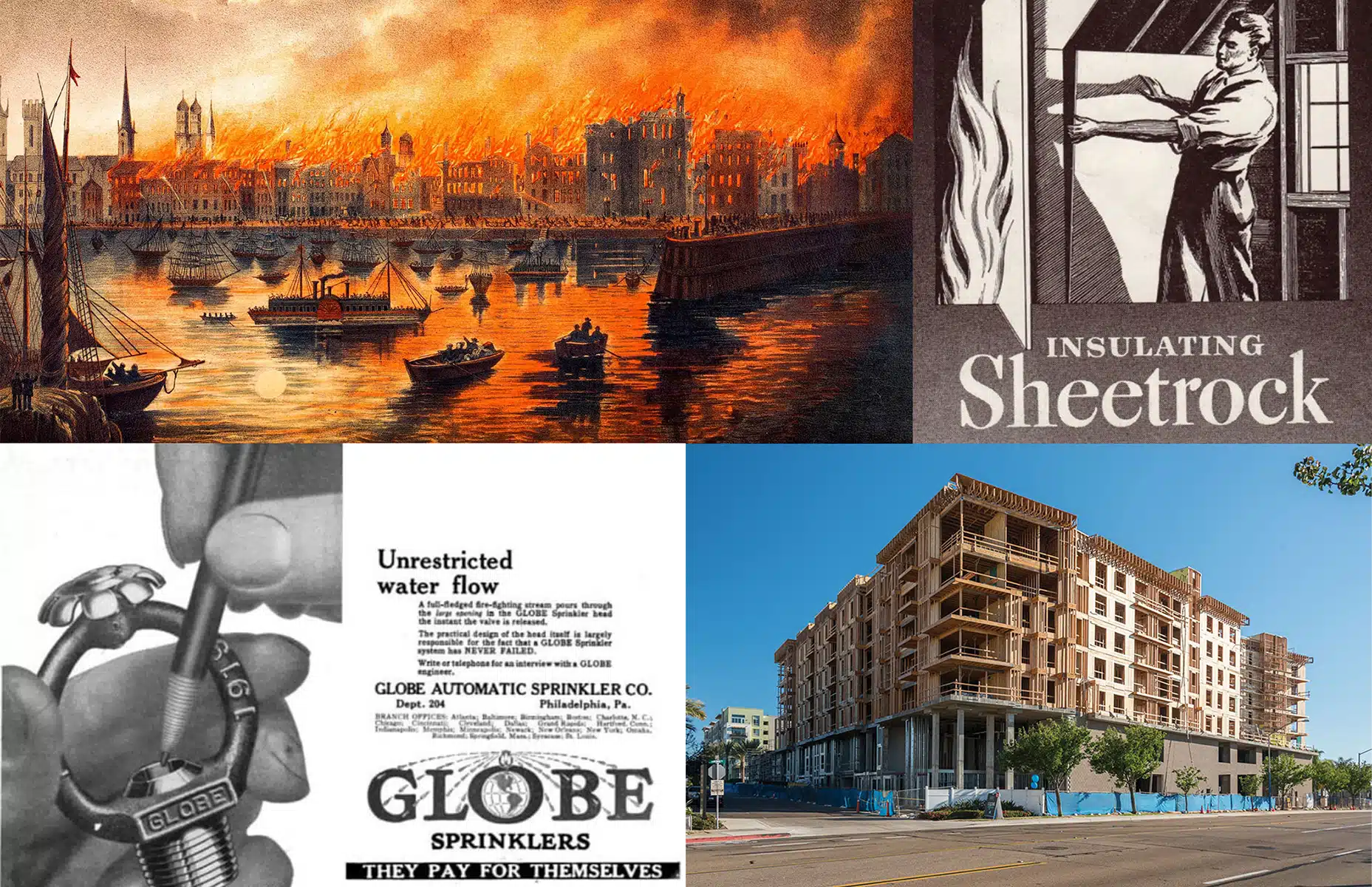

An Abbreviated History of Building Codes: on the topic of stick-built, we need only address the issue of ‘fire resistance’. It was the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 that galvanized the need to establish formalized building codes for life-safety. The fire had destroyed thousands of wood, ‘balloon-frame’ buildings, leading to a ban on stick-frame buildings in dense urban neighborhoods. Over time, building codes relating to fire life-safety continued to evolve as insurers and manufacturers lobbied for more ‘performance-based’ codes emphasizing lab-determined fire resistance ratings and new technologies such as fire sprinklers. This had major implications for wood framing. Additional life-safety considerations, such a seismic, also factored into the considerations around wood framing, and by 1970, the Uniform Building Code [UBC] made it possible to build 4-stories of wood famed construction atop a concrete podium in a majority of seismic-zoned, jurisdictions. And, by 2000, the publication of the International Building Code [IBC] offered various new interpretations of fire resistant / suppressive material and system configurations that paved the way for today’s stick-build construction. Notwithstanding, there are still concerns relating to fire resistance with stick-build construction but they pertain to the construction phase—prior to the completion of fire rated assemblies and functional sprinkler systems. While the number of such fire instances have been few and far between, additional measures still need to be developed, tested, and codified as part of the construction means and methods.

Construction Materials / Methods and Environmental Impact: there is no IDEAL material or method of construction. Each has its own implications for depleting natural resources, increasing environmental degradation, and contributing to a host of byproduct-waste streams—just to mention a few of the potential environmental impacts. Wood frame construction is typically contrasted with steel and concrete, generally along three lines: extraction + manufacture, embodied energy, and potential for recycling + re-use. In terms of extraction + manufacture, wood frame construction is largely a sustainably farmed industry—aka: a renewable resource. As a whole, the industry utilizes 90% of extracted resources, be it in the form of direct products or biomass byproducts used to power production facilities. This is a figure neither steel nor concrete can come close to matching. In terms of embodied energy, the production of wood frame construction components and associated transportation impacts also trends more efficiently than those of steel and concrete. That said, while farmed forests are inherent ‘carbon sinks’, considerable amounts of carbon can be released in the process of milling lumber. Whereas, concrete, depending on the use and disposition within a building system, can effectively function as a carbon sink, absorbing CO2 from the surrounding environs. Finally, in terms of recycling + re-use, all three systems have a host of potential options that continue to evolve. In summary, the prospects for wood frame construction as an environmentally sound building option are positive and continually improving.

1700 Duke Street | Alexandria, VA

For MV+A, our own experience with stick-built goes back to the early 2000’s. 1700 Duke Street, in Alexandria, Virginia was a project of many firsts.

It was THE first stick-built project of its kind in the Washington area, having been approved with code modifications to the old BOCA Codes prior to Alexandria’s formal adoption of IBC. The modifications introduced the concept of a horizontal fire wall, something never allowed under the BOCA codes. The horizontal firewall, the basis for podium construction, allowed us to switch construction types above the second floor podium, introducing Type V wood stick-built construction. It was the first stick-built multifamily project for the client, the JPG Companies, as well as for the builder, Clark Construction. Additionally, it was the first such project in the region with a major grocery tenant anchoring a mixed-use podium project.

1700 Duke Street started the mixed-use practice at MV+A, merging our retail expertise with our extensive multi-family experience. Our design and planning formulas, focused on creating the best retail and sidewalk experiences while solving the myriad technical challenges from loading to exhaust have made MV+A an industry leader in complex mixed-use, stick-built projects.

In Part II of our CODES, COSTS + CRAFT series: Sticking Up for Stick-Built, we will dive deeper into the great debate surrounding stick-built and the proactive approaches we have developed at MV+A in our nearly two decades long experience working with this building type.