HOUSING FUTURES | Next Steps

In this next installment of our Housing Futures series, we look at the ‘point access block’ movement that has been captivating the imaginations of many in the housing sector with burgeoning success stories in Seattle, California, Colorado, and elsewhere. Closer to home, several municipalities in Virginia have recently been considering code provisions / amendments to allow for denser, single-stair multifamily projects but the jury is still out, so to speak.

Herein, we will consider the basics of point access block buildings, evaluate their implications for addressing a range of housing and sustainability / resilience issues, as well as their potential for spurring development opportunities.

U.S. and Them

In the most basic terms, this is a discussion of dueling multifamily housing types: the North American ‘double loaded corridor’ type and the single-stair, ‘point access block’ type utilized across the globe—from South America to Europe and the UK, and across the whole of Asia.

While the double loaded corridor is not restricted to North America, it’s use here, for multifamily purposes, is inextricably tied to longstanding fire / life safety codes that many consider to be either outdated, excessive, or both. It has also yielded a multifamily building type that has become a source of much debate in just about every community where it has been deployed: the 5-over-1 multifamily residential building.

Without digressing too much, the double loaded corridor owes its relevance and ubiquity to the ‘minimum two means of egress’ fire code requirement, wherein two or more opposing ‘fire stairs’ are located at opposite ends of a corridor—providing occupants with two options of escaping a fire on any given floor. While this may once have seemed a very sound, common sense strategy, more modern codes mandating fire rated building assemblies and separations, fire sprinklers, pressurized stairwells, and other fire / life safety measures have made the ‘minimum two means of egress’ code requirement something of a redundancy.

Source: larch lab | Michael Eliason

Diagram showing height restrictions for single-stair multifamily buildings across the globe; yellow represents 3-stories while green represents 6+stories. Currently, in most U.S. municipalities, in the single-stair multifamily building type is allowed up to 3-stories with no more than 4-units per floor.

Source: World Fire Statistics Center

Despite our elaborate fire codes, the U.S. still exceeds a majority of countries—where single-stair multifamily residences are the norm—in the number of building fire deaths.

Clearly this is not a simple equation to solve and any substantial changes to the codes will involve considerable analysis and consensus across a range of municipal agencies at the local and state levels and, ultimately, will need to prompt changes to the International Building and Fire Codes [IBC + IFC] if the single-stair multifamily type is to achieve widespread adoption in the U.S.

A Side-By-Side Comparison

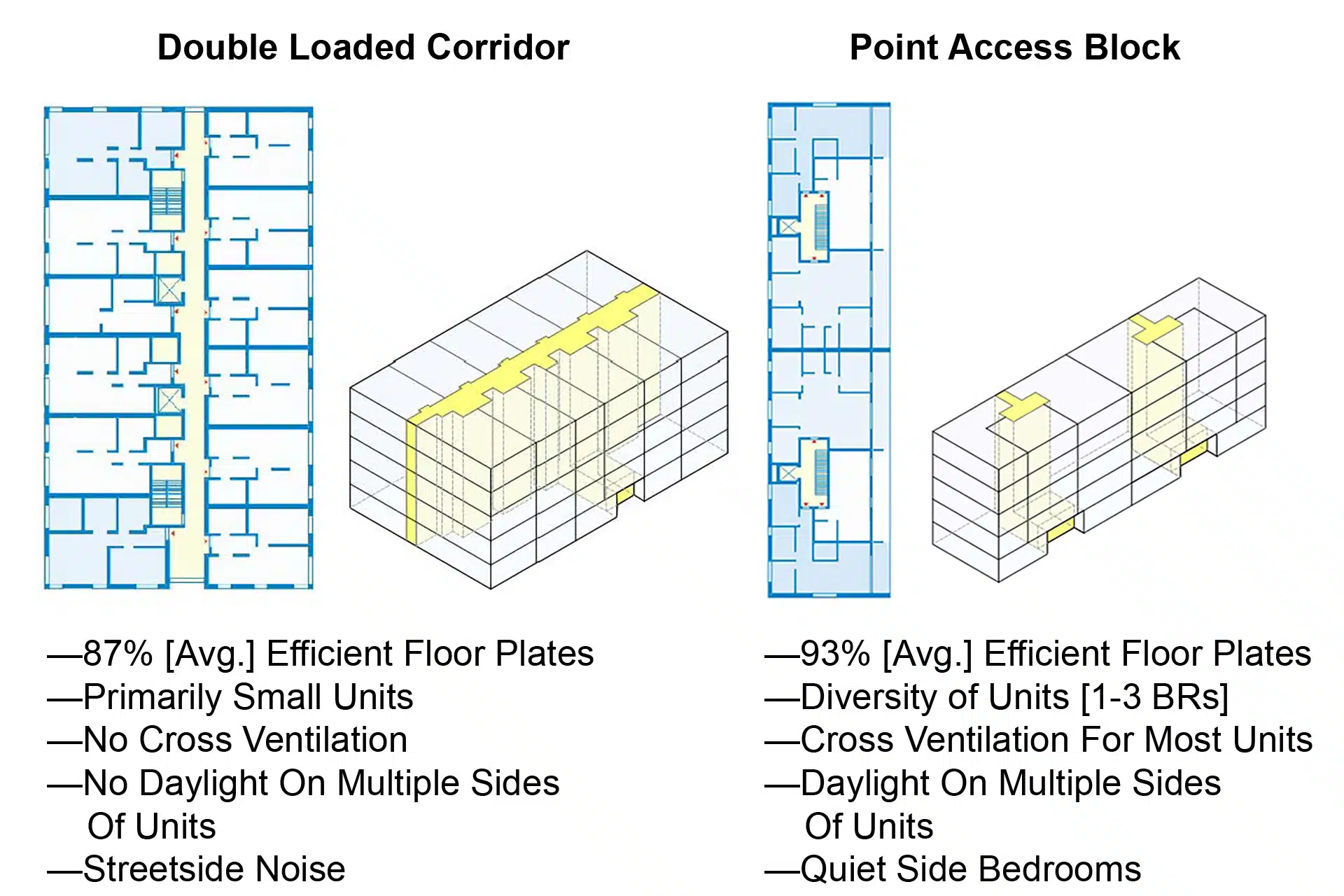

Setting aside the fire / life safety question, there are a whole host of advantages to be gained from utilizing the single-stair multifamily building type.

Let’s begin with a side-by-side comparison:

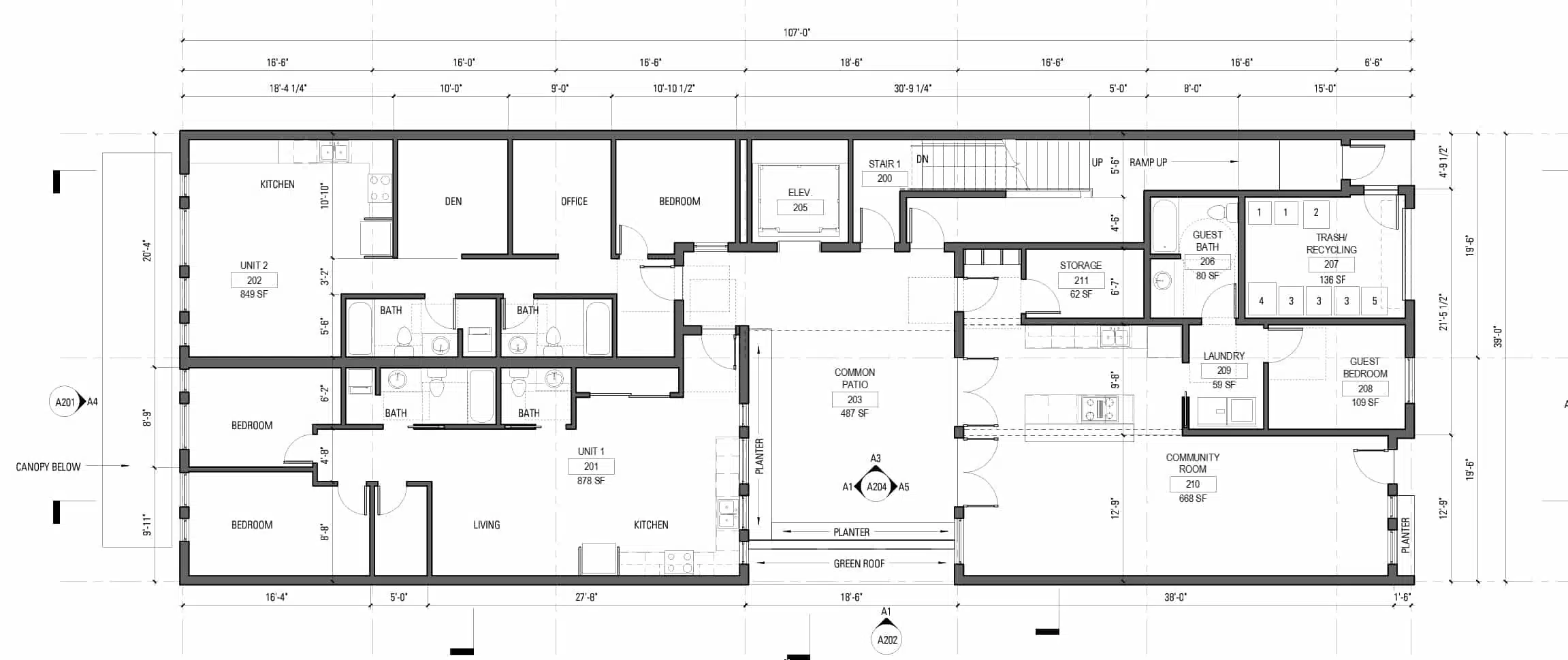

Relative to the current, ongoing housing shortage, one of the most critical—oft overlooked—issues relates to housing ‘options’. Meaning to say: choices; the vast majority of new multifamily housing units being added to the market are 1-bedroom and studio units—not exactly ideal for families. In part, this may be attributed to the fact that opportunities for larger units in a double loaded corridor building are most easily accommodated at the building corners.

Because most units within a single-stair multifamily building span the full depth of the building, the opportunity for larger units is significantly greater. Considering the examples above, it might be argued that the single-stair type is only suited for certain site parameters. In actuality, this type is considerably more adaptable to site constraints than the double loaded corridor type.

The diagrams above demonstrate not only the efficiency and flexibility of the single-stair multifamily type, but also illustrate the implications for reduced building mass / embodied energy + carbon, reduced energy consumption [vis a vis daylighting + cross ventilation], and increased open space and opportunities for blue / green infrastructure and garden space.

When it comes to actual, built precedents, there aren’t many examples of completed point access block projects in the U.S. that are more than 4-stories in height and that demonstrate the sort of density to rival most 5-over-1 multifamily developments. The best examples are to be found in Europe.

The recently completed urban quarter of Neckarbogen, in Heilbronn, Germany is an optimal example. Virtually all of the multifamily developments are composed of point access block buildings. There is a very robust mix of units with studios and 1-bedrooms accounting for under 20% of the total. Additionally, there is a well thought out distribution of market-rate, subsidized, senior, and other types of housing. Projects range in height between 5- and 12-stories—the latter a mass timber project. District codes mandate the utilization of passive building design strategies including natural ventilation. Air conditioners are a rarity and are typically mobile units purchased by tenants. Additionally, there is an abundance of greenspace, often designed to accommodate storm water management and other blue / green infrastructure capacities.

This sort of development is not unique in Europe; it is more the norm than the exception. And while sustainability and resilience are top priorities, there is still considerable attention paid to the street wall and to what is referred to as ‘fine grain’ or ‘granular’ urbanism—the creation of human-scaled, materially expressive, and vibrant building forms that contribute to dynamic placemaking.

Unlocking Opportunity

One of the most costly aspects of developing multifamily housing is land assembly—the combining of properties to amass a developable parcel. In the U.S. the average cost of this activity is 10-20% of the overall project costs. In a city like Los Angeles, it can be upwards of 40%. In neighborhoods where land assembly is simply not an option, point access block strategies can unlock sites viewed as unfit for multifamily development.

In Washington State and California, a variety of single-stair strategies have been developed for urban infill sites varying in width from 25’ to 50’ and from 100’ to 150’ in depth, with the intention of unlocking sites deemed unfit for multifamily development absent larger land assembly options.

This approach typically utilizes the central stair as a court to facilitate daylighting and cross ventilation as well as promoting community interaction. Given the compact circulation area and factoring-in a broader demographic resulting from a mix of unit sizes, the potential for positive community building is likely to be richer and more rewarding than what one might expect within the homogenous, doubled loaded corridor experience.

Next Steps?

To be clear, the intention here is not to suggest that the double loaded corridor multifamily housing type is obsolete or even less effective than the point access block type. On the contrary, 87% efficiency is still plenty efficient and the 5-over-1 still has plenty to offer. Rather, the point access block should be viewed as a transformative new typology for confronting a variety of housing issues, well suited to the missing middle movement discussed in detail in Part I of this series. Still, there are numerous, plausible factors that make the adoption of point access blocks a challenge.

In sheer economic terms, the costs associated with a noteworthy increase of elevator requirements is understandably a concern. The most commonly cited trade-off here is the cost savings associated with increased building efficiency and the overall reduction of building mass. In Europe, where air conditioning is considerably less prevalent, there is substantial cost savings associated with the reduction of MEP systems. Additionally, with the elimination of rooftop units, blue / green roofs can reduce energy consumption and provide stormwater management. Of course, it is highly unlikely that Americans will forgo AC in lieu of cross ventilation and the added benefits of green roofs. Parking is another major cost factor. A majority of 5-over-1 buildings utilize above ground, pre-cast parking structures. A majority of point access block buildings either don’t have parking or the parking is below grade, which comes at a premium. That said, point access blocks are better-suited to prefabrication and other emergent new construction means and methods. This should add to the potential cost benefits.

In terms of zoning and building codes, the adoption of single stair, multifamily building types will not happen overnight. But the progress being made out west is encouraging and lending meaningful momentum to an approach that could go a long way in addressing our current housing crisis in this country.

Source: larch lab | Michael Eliason

It should be noted that much of the information contained herein is thanks to the efforts of Michael Eliason, founder of larch lab. After working for several years in Freiburg, Germany, Michael has been applying his experience with point access block housing, passive building design, and other lessons learned towards advancing the state of housing and community building here in the US and Canada. Not unlike Daniel Parolek’s / Opticos’ efforts with ‘Missing Middle Housing’, Michael has become the go-to-guy on point access block housing. We’re grateful for his efforts and will continue to spread the word!